The Role of Public Libraries in a World of Digital Reading

I’m looking out at the world from Sweden, a 10 million country in the wealthy north Europe, where ebook and audio book retail has had an increase of 50 % of sales per year 2015-2018. The Swedes’ digital book consumption has now reached similar levels as the early adopter markets, USA and UK, where digital reading for a while now has represented 30-60 % of all book consumption, depending on which metric you prefer.

In many markets monthly subscription (rental) is a growing model for trade books – meaning that the consumer pays 20 EUR or so for an “all you can eat” offer. This model first became dominant in music and video services like Spotify and Netflix, and is now spreading to other media.

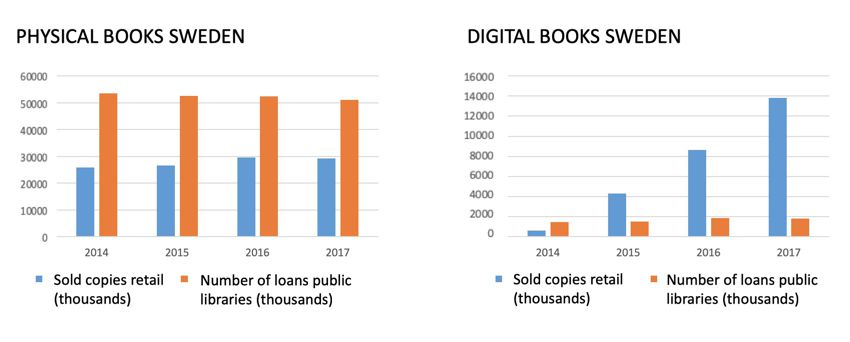

At the same time as retail of digital books has grown rapidly in my country, the digital ebook and audio book services provided by public libraries haven’t been able to keep up. It seems this is true also in many other markets.

Are we headed for a point where public libraries become irrelevant as providers of books?

I think we need to look at the core purposes of libraries to answer this question:

A core purpose of public libraries is to support reading and create equal conditions for access to information, reading materials. This is to help people learn, work, conduct research on various levels and to enjoy stories told by masters of the written word. The activity of reading helps building cultural identity and gives strength to citizens of the democratic society – dictators don’t like public libraries. Therefore, lending out books in a way that is relevant to people is an important tool for public libraries to fulfill their purpose. Slipping out of digital reading therefore seems risky.

Libraries have prioritized target groups. These are all relevant in the conversation about digital books and library services to promote reading:

- Children and young people. This group is increasingly online on a daily basis, but there are signs that reading skills and book reading habits decline in some places. Book reading is under heavy competition from other digital sources of entertainment such as games and video. Can we make reading great again?

- People with disabilities – For this group who are traditionally served by specialized libraries run by the blindness movement, digital availability and accessibility of content and services in the mainstream is a game changer. If that is true for retail, it should also be true for public library services.

- Immigrants, refugees and Minorities – Often low resourced people and in risk of marginalization. Limited access to books in a first language and weak reading traditions creates an especially challenging mix. Access to physical collections in libraries depends on geographic location and the right to first language reading is hard to live up to using local council run physical libraries.

- Socio-economically challenged – Investing in digital books is low priority for people who struggle to make ends meet. For this group free to use public library services are evidently important.

Lending digital books is not like physical and libraries are now regarded as retail channels by publishers. The copyright legislation makes conditions around digital books different from those of physical books – and in reality most library lending of popular fiction is based on libraries renting books from commercial aggregator companies rather than buying and owning copies for lending. The shift of model from owning copies to renting has waved the power balance. In the digital domain the publishing companies exercise much more control of what ends up in libraries. If a publisher sense that library lending is not good for business, they can easily remove their books from the library’s digital book shelves by for instance rising the price per loan above a pain level, public libraries can thereby not afford high service levels on best seller titles. Since content is king, the attraction power of the library offer in terms of content may thereby have paled a bit in comparison to what was possible with physical books.

On the other hand libraries can now – like online retail – be open 24-7, with a free to use service for everyone with a device and a library card. There seems to be very little evidence that library lending reduces commercial sales, but this is a much debated topic. Publishing companies have tried out embargos against library lending of important titles to test what the impact is, but without clear results it seems.

“There is a lack of appreciation of the great value that authors, agents and publishers receive by having their ebooks, digital audio books, and books available for discovery and potential use in public libraries” – Overdrive CEO Steve Potash Library Journal Sept 06, 2018

Public library collections are about breadth, depth and memory. Big city libraries or consortias of many small libraries have millions of unique physical titles, with great coverage of the backlist and out of retail books. They typically have substantial collections of books in different languages. The lack of top 100 best sellers in public libraries doesn’t have to be a great problem. One strength of libraries is their active curation and ability to provide many alternative titles, possibly lift titles that have cooled down in retail.

During research work conducted in 2018 I benchmarked some international examples of digital library services that support reading and serve ebooks and audio books to large populations. What I found was truly inspiring to me.

The three most successful major services I could find were Denmarks eReolen, Onlinebibliotheek.nl covering the Netherlands and New York public library’s SimplyE. All three serve millions of people, use library owned infrastructure and develop their service using small multifunctional teams with user orientation and open source development in their DNA. Most successful is eReolen Denmark. Astonishing 6% of Denmarks population have checked out a book through them during the past 12 months.

eReolen, Onlinebibliotheek and SimplyE seem to have come far in reinventing what a digital public library can be – and have found a position where they can co-exist alongside digital publishing rather than fighting them. The scale that they have, serving whole nations or a large city as in NYPL’s case, enables them to approach negotiations with content providers with their head held high.

To scale up public libraries will in many instances require political awareness and leadership, since public libraries are often small local independent actors with no nation-wide governance. It sounds boring, but my major conclusion is that organization of public libraries or rather the lack thereof is the core problem and where it typically fails.

So why do I think innovative public library services are so important? Well, for one, universally designed library services have a great potential to also be inclusive and welcoming to people with disabilities. In the long run, copyright exception based services such as the classic “library for the blind” have the potential to be supported or even replaced by inclusive mainstream retail and library services, in the process opening up a much more diverse range of content to an audience who have historically faced limited reading options.

Many thanks to Jesper Klein for this article which is based on his presentation “Marrakesh treaty in action” at Oodi library Helsinki Finland March 2019